|

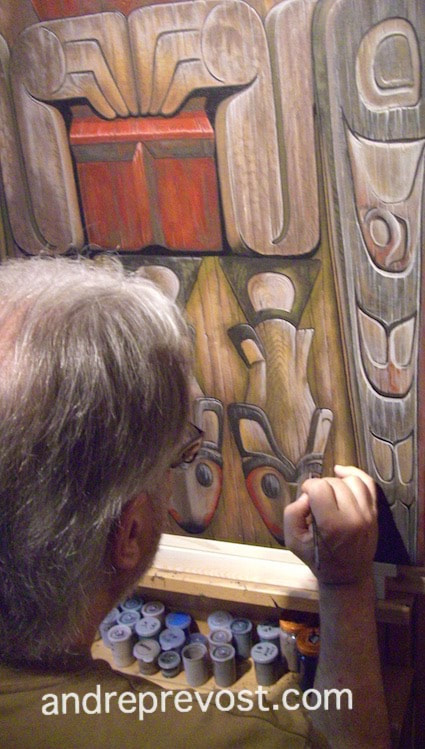

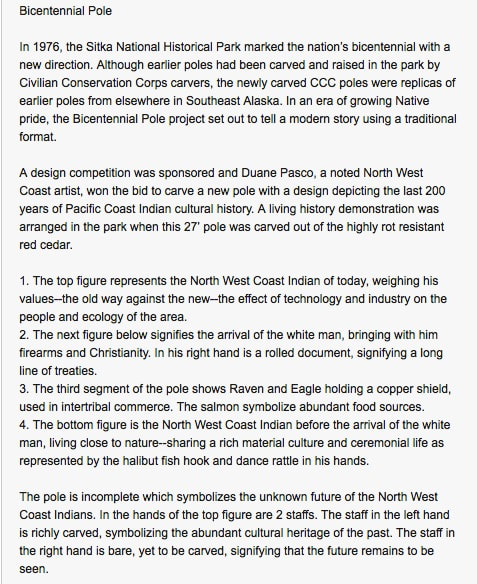

Raven & Eagle Shield, 2015 24” x 48” x 1.5” Detail from the Bicentennial Totem Pole in Sitka National Historical Park, Alaska, ‘depicting the last 200 years of Pacific Northwest Coast Indian cultural history’. Carved by Duane Pasco in 1976. This park is in honor of the Battle of Sitka, the site of the battle between the Tlingit, Aleut/Koniag and the Russians in 1804. This battle marked the beginning of the Russian ruling Sitka for many years. This section presents the Tlingit, Aleut/Koniag before the white man’s arrival (you can see the shoes of the white man depicted over the heads of the Raven and Eagle. There is such a striking sense of balance in this section. Also included is a ‘Copper’. “Coppers are an essential part of the potlatch economy of the Northwest Coast, particularly among the Kwakwaka'wakw. These beaten and decorated sheets of copper are important symbols of wealth, which in turn reflects relative degrees of status and power. Each copper was individually named.”(Codere). The salmon symbolize abundant food sources. ______________________________ When I came across the images of this Alaskan totem online, I was struck by its story and especially by the second section from the bottom, in its powerful balance. At first, I had only seen this one section and was unsure what I was seeing on the tops of the Eagle and Raven’s heads. When I found the full totem, the significance of what those were made the pre-white man section even more powerful. I loved how this one cropped image, even though orderly and symmetrical, was under the weight of the impending changes and disorder to come. I decided to use a 24”x 48” canvas and cropped the image to capture the essence of this totem section, and again, to leave out the surrounding detracting landscape. This meant that I had to crop the beaks of the Raven and Eagle, while still maintaining the strength of each face. The first challenge in preparing this design was the key stoning of the photograph. Because the composition of the totem was so symmetrical, I used a forced grid pattern to correct the key stoning at the top. This meant that the details at the top of the canvas would require some adjusting to compensate for the stretching. Forced grid pattern? I hadn’t tried this before. I prepared the usual grid pattern on the photograph, but instead of following the rectangle of the photograph, I followed the side edges of the totem itself. On the canvas, I drew the regular grid pattern on the canvas. Then I transferred the image grid design onto the canvas grid, which automatically opened up the upper section. With some adjustments to shapes of the head and eyes, it had achieved a focal point on the totem as though you were standing at its level, and everything was perfectly in balance. A caution is that this forced grid will only work on some compositions, not all. As I began to develop this painting, the other choice that I made was to adjust the wing and cheek on the right hand side. On the actual totem, the level of deterioration and patina on the south side was more pronounced. But in order to maintain that balance and order, I toned down the amount of graying and loss of paint on the southern wing and southern cheek of the Eagle’s face. This way, the viewer’s eye remains in the central composition and not pulled the right of the canvas and working against that calmness and balance. There are so many incredibly beautiful details in Duane Pasco’s design and carving. I am always struck by elements common in the works from other areas around the world. In this totem, the hands holding the copper have similarities to the ancient carvings from Central America for example. What also tweaks my curiosity is how, somewhere at the core of all humans, there are those similarities within ancient traditions, such as the shape of the eye, etc. I had decided to do this painting late in 2014, knowing that I had my first exhibition in late January. I wasn’t sure whether I would be able to complete it in time. I managed to put in long hours, and very long days in the end, in order to complete it in time. It turned out to be much more labour intensive then I had expected at the start. It was crucial that I capture the truth of the totem. So many layers, so many glazes. So many wood grains, wood textures, and carved surfaces responding to aging in their own way, and to the light and shadows. Not having a proper wall easel, which can be adjusted to paint the bottom sections, I had to improve in order to lift the canvas to save my lower back. There was as much detail at the bottom. (This is part of my goal of finally getting into a house on the Island where I can have the room to set up my studio space, as I need.) I know I could have gone on and on in the minutia of the details, but like the other paintings, there is that point when your instincts tell you that it is time to set the brush down. Has been purchased as part of a private collection in West Vancouver, BC

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed